The pediatric assessment triangle is one of the most important tools in emergency care because it gives clinicians a rapid, reliable first impression of a child’s condition. It only takes a few seconds, yet it offers powerful insight into whether a child is stable, in respiratory distress, in shock, or at risk of rapid deterioration. Unlike a full physical exam, the PAT relies entirely on visual and auditory cues. This makes it especially valuable in the moments before vital signs are collected or when a child cannot communicate what is wrong.

This guide explains how the pediatric assessment triangle works, what each component means, and how to apply it in real clinical settings. It also includes practical tips and common mistakes that new clinicians often overlook. At Rego Park Diagnostic & Treatment Center, pediatric clinicians use structured assessment tools like the PAT to ensure fast, accurate evaluation for children during urgent or routine visits.

What Is the Pediatric Assessment Triangle?

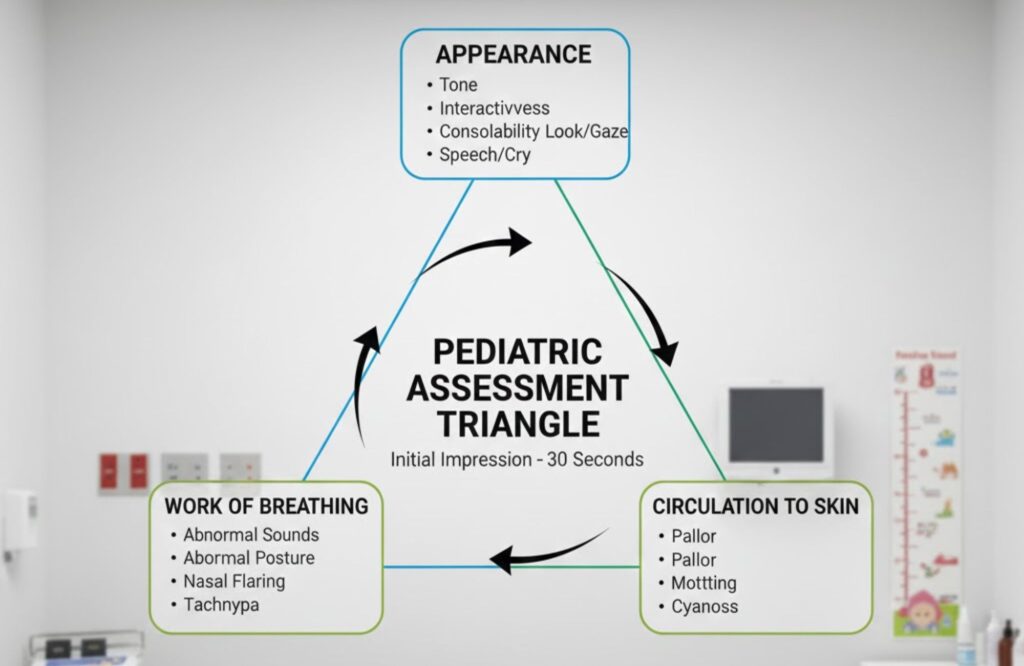

The pediatric assessment triangle is a rapid visual assessment used to determine whether a child is sick or not sick at first glance. It evaluates three areas: appearance, work of breathing, and circulation to the skin. When combined, these three observations give clinicians an immediate sense of the child’s overall stability.

The PAT was created to help healthcare providers form a quick impression before touching the patient. It is now widely used in pediatric emergency departments, EMS systems, urgent care clinics, and other settings where quick decisions matter. Because it does not rely on equipment, it can be performed anywhere. This includes prehospital environments and situations where vital signs are delayed or difficult to obtain.

Why the Pediatric Assessment Triangle Matters in Child Assessment

Children often compensate for illness until they suddenly decline. This means that relying only on vital signs may delay recognition of life-threatening problems. The pediatric assessment triangle fills this gap by highlighting early signs of respiratory distress, shock, circulatory compromise, or altered mental status.

It is especially useful when:

- A child is too young to describe symptoms.

- A caregiver cannot provide a reliable history.

- A child is developmentally delayed or nonverbal.

- The environment is chaotic, and rapid decisions are required.

The PAT does not replace the ABCDE assessment. Instead, it guides the urgency and direction of care. Once abnormalities are identified, clinicians move immediately into airway, breathing, and circulation management.

Components of the Pediatric Assessment Triangle

The pediatric assessment triangle has three interconnected components. Each one reveals critical clues about perfusion, respiratory effort, neurological function, and overall severity of illness.

Appearance: Using the TICLS Framework

Appearance reflects the child’s neurological status and general interaction with their environment. To evaluate this component thoroughly, clinicians use the TICLS framework: Tone, Interactiveness, Consolability, Look/Gaze, and Speech/Cry. Each element helps determine whether a child has a normal mental status or an altered neurological state.

Tone

A healthy infant or child typically shows good muscle tone, spontaneous movement, and the ability to resist examination. When muscle tone is unusually floppy, rigid, or absent, it may suggest neurological problems, severe infection, metabolic imbalance, or impending respiratory failure.

Interactiveness

A well-appearing child is curious, alert, and responsive to the surroundings. They may reach for objects, track movement, or make eye contact. Poor interactiveness can indicate fatigue, shock, hypoxia, fever, or altered mental status.

Consolability

Children who can be soothed by a caregiver generally have adequate neurological function. A child who cannot be comforted or who fails to respond to familiar voices or touch should raise concern for pain, infection, dehydration, or systemic illness.

Look/Gaze

Normal gaze includes stable eye contact, visual tracking, and appropriate head movement. Abnormal gaze, including staring, sunsetting eyes, or fixed gaze, may signal seizure activity, head trauma, or metabolic disorders.

Speech/Cry

Age-appropriate speech or cry is a key sign of adequate airway patency and neurological status. A weak cry, hoarse voice, or minimal vocal response can indicate airway obstruction, respiratory failure, or decreased consciousness.

Together, these patterns help clinicians determine whether immediate intervention is needed or if the child is stable enough for further evaluation.

Work of Breathing: Early Signs of Respiratory Distress

Work of breathing describes the child’s respiratory effort. Increased or decreased respiratory effort can both indicate a life-threatening issue. Before listing the signs, it’s important to understand that increased work of breathing is often the earliest indication of respiratory distress. Children may compensate for a long time before their breathing suddenly becomes inadequate.

Observations Include:

- Abnormal airway sounds: Stridor suggests upper airway obstruction. Wheezing indicates lower airway narrowing. Grunting signals the child is struggling to keep alveoli open.

- Abnormal positioning: Tripoding or sitting upright is common in respiratory distress as the body attempts to maximize airflow.

- Retractions: Supraclavicular, intercostal, or substernal retractions show increased breathing effort.

- Nasal flaring: A sign of hypoxia in infants and young children.

- Head bobbing: Infants may bob their head with each breath when extremely fatigued.

Table: Signs and What They Mean

| Finding | What It Suggests |

| Stridor | Upper airway obstruction |

| Wheezing | Narrowed lower airways |

| Grunting | Severe respiratory compromise |

| Retractions | Increased work of breathing |

| Tripod position | Attempt to improve airflow |

When any of these signs are present, clinicians should move quickly to assess airway patency, ventilation, oxygen needs, and potential causes such as asthma, infection, trauma, or choking.

Circulation to Skin: Recognizing Perfusion Issues

Circulation to the skin reflects cardiovascular stability. The skin is one of the first areas to show reduced blood flow when the body begins compensating for shock or hypoxia.

Before listing the findings, it’s important to understand that children compensate through increased heart rate and peripheral vasoconstriction long before they exhibit hypotension. Skin appearance often changes earlier than blood pressure.

Key Indicators:

- Pallor: Indicates reduced perfusion, anemia, or shock states.

- Mottling: A patchy, marbled skin appearance caused by uneven blood flow.

- Cyanosis: Blue discoloration signaling inadequate oxygenation.

- Delayed capillary refill: More than two seconds suggests poor perfusion.

It is also important to consider normal variations in skin tone. On darker skin, clinicians should check mucous membranes, nail beds, lips, and the palms for discoloration or cyanosis.

Category Breakdown and What Each One Means

- Normal: Appearance, work of breathing, and circulation are all normal. The child is likely stable and can undergo further evaluation at a routine pace.

- Respiratory Distress: Work of breathing is abnormal, but appearance and circulation are normal. The child is compensating and needs monitoring and treatment, such as bronchodilators or suctioning.

- Respiratory Failure: Both appearance and breathing are abnormal. The child is tiring out or becoming hypoxic. Immediate airway and ventilation support are required.

- Shock: Circulation is abnormal with signs like pallor, mottling, or poor capillary refill. The child may have tachycardia, delayed perfusion, or altered mental status.

- CNS/Metabolic Dysfunction: Appearance is abnormal due to an altered mental state or tone, but breathing and circulation may appear normal. Hypoglycemia, seizures, or metabolic disorders may be the cause.

- Cardiopulmonary Failure: All three components are abnormal. This is a life-threatening emergency requiring immediate CPR, ventilation, and advanced interventions.

How to Use the Pediatric Assessment Triangle in Real Practice

Using the PAT begins the moment a clinician sees the child. No equipment is needed. The process can be described in a few clear steps:

- Observe appearance and neurological status using the TICLS framework.

- Evaluate work of breathing by looking for retractions, sounds, and positioning.

- Assess circulation to the skin by checking color, temperature, and perfusion.

- Identify patterns that match common illness categories.

- Move into the ABC assessment to stabilize airway, breathing, and circulation.

This approach ensures early recognition of airway obstruction, respiratory distress, shock, dehydration, infection, hypoglycemia, seizures, or trauma.

Common Mistakes When Using the Pediatric Assessment Triangle

Three common mistakes can lead to misinterpretation of the PAT. First, clinicians sometimes mistake a quiet child for a stable one. A child who is unusually silent, minimally responsive, or limp may be in respiratory failure or shock. Second, clinicians may overlook subtle work of breathing signs, especially in dim lighting or crowded environments. Slight nasal flaring or mild retractions may be early indicators. Finally, skin color can be misinterpreted in children with darker skin tones, leading to missed signs of cyanosis or poor perfusion.

Pediatric Assessment Triangle vs ABCDE Assessment

The PAT and the ABCDE assessment serve different purposes. The pediatric assessment triangle is the first snapshot, providing an immediate sense of urgency. The ABCDE assessment is the hands-on, systematic evaluation that follows.

PAT answers the question: “Is this child sick?” ABCDE answers: “What should I treat first?” They work together, not separately. After identifying abnormalities with the PAT, clinicians transition directly into airway management, ventilation support, perfusion correction, or neurological evaluation.

Conclusion

The pediatric assessment triangle offers a fast and reliable way to determine whether a child is sick or stable. By evaluating appearance, work of breathing, and circulation to skin, clinicians gain early insight into respiratory, circulatory, or neurologic compromise. When used correctly, the PAT supports quick recognition, timely interventions, and safer care for infants, children, and adolescents.

At Rego Park Diagnostic & Treatment Center, our pediatric team uses structured assessment methods like the PAT to ensure accurate, child-focused evaluation during every visit. We are committed to providing safe, attentive care for families in Queens. Contact us today to schedule an appointment or learn more about our pediatric services.

FAQs

When is the pediatric assessment triangle performed?

The pediatric assessment triangle is performed the moment a clinician first sees the child, often from the doorway or upon initial contact. It is used before touching the patient to decide whether they are sick or not sick and to determine how quickly care is needed.

What are the components of the pediatric assessment triangle?

The components of the pediatric assessment triangle are appearance, work of breathing, and circulation to the skin. Together, these three visual observations provide a rapid overview of a child’s neurological status, respiratory effort, and perfusion.

What is the triangle assessment of a child?

The triangle assessment of a child refers to the pediatric assessment triangle, which is a quick, equipment-free method for forming an initial impression. It helps clinicians identify signs of respiratory distress, respiratory failure, shock, or neurological compromise within seconds.

What does ABC mean in the Pediatric Assessment Triangle?

It refers to how the PAT guides the urgency of moving into the ABC (airway, breathing, circulation) assessment. PAT is the first visual impression, and ABC is the hands-on evaluation that follows when instability is detected.